Full Text

Introduction

Urticaria is a heterogeneous skin disorder, commonly known as hives, characterized by raised, well-defined areas of erythema, swelling, and itching [1]. Lesions can appear on any part of the body and typically resolve spontaneously without leaving residual marks or scars [2]. Urticaria, also referred to as nettle rash, classically presents as wheals on the skin [3].

Urticaria is broadly classified into two main categories: acute and chronic urticaria, as well as physical urticarias. Acute urticaria refers to lesions that persist for less than six weeks and occur randomly without an identifiable physical trigger. If the lesions persist for six weeks or more, the condition is termed chronic urticaria (CU). Urticaria can significantly impair the quality of life in many patients [4]. A number of individuals report food allergies as a contributing factor to their symptoms [5].

Monosodium glutamate (MSG), also known as monosodium L-glutamate or sodium glutamate, is the sodium salt of glutamic acid and is widely used to enhance the natural flavour of foods. It was first identified as a flavour enhancer in 1908 by Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda, who found that seaweed-based soup stocks contained high levels of this substance. MSG elicits a distinctive taste known as umami, considered the fifth basic taste, enhancing the complex flavours of meat, poultry, seafood, and vegetables. Following Ikeda’s discovery, MSG began to be commercially produced from seaweed. Today, it is manufactured through bacterial fermentation using starch or molasses as carbon sources and ammonium salts as nitrogen sources. In some individuals, large quantities of ingested MSG have been reported to cause physical symptoms such as burning sensations, facial pressure or tightness, and tingling—collectively referred to as the MSG symptom complex or, informally, “Chinese restaurant syndrome.”

The skin prick test (SPT) is a well-established diagnostic method for identifying IgE-mediated allergic diseases. It provides evidence of sensitization and aids in confirming suspected type I hypersensitivity reactions. SPT is minimally invasive, yields immediate results [6], and is particularly valuable when other investigatory approaches fail to identify the allergen [5]. For detecting allergens and specific IgE antibodies, SPT is more sensitive, specific, cost-effective, and user-friendly than many alternative methods.

Therefore, this study was undertaken to determine the skin prick test positivity to monosodium glutamate in adult urticaria patients and to raise awareness about the presence of MSG in foods and food products widely available in the market today.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Dermatology Outpatient Department of Jubilee Mission Medical College and Research Institute, Thrissur, to assess the prevalence of skin prick test positivity in adult patients with chronic urticaria over a period from July 2022 to December 2023. The study has been approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Utilizing consecutive sampling, the study included 120 participants, as determined from a sample size calculation based on previous research showing a 68.8% sensitization rate to allergens in chronic urticaria patients in South India. Inclusion criteria encompassed adults of either sex diagnosed with chronic urticaria, while exclusion criteria included conditions such as asthma, pregnancy, history of anaphylaxis, and the use of medications that could interfere with test results. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

The positive control used in the skin prick test was histamine phosphate solution, and the negative control was buffered saline in a glycerol base.

Skin prick test procedure

Before performing the skin prick test, the procedure, along with its potential risks and consequences, was clearly explained to the patient to reduce anxiety. An emergency kit was kept readily available and included an adrenaline injection, antihistamine injection, tourniquet, sterile syringes and needles, an oxygen cylinder with a face mask, and an artificial respiration kit.

The volar aspect of the left forearm—approximately 2 cm from the wrist and the cubital fossa—was thoroughly cleaned with soap and water. Purified allergen extracts, along with positive and negative controls, were prepared in advance. The controls were applied first, followed by the allergen. Using a sterile lancet, the skin was gently pricked obliquely through each allergen droplet at a depth of 1 mm for one second. Adjacent test sites were spaced at least 2 cm apart to avoid overlapping reactions. The lancet was properly wiped between pricks to prevent cross-contamination. Excess allergen droplets were carefully blotted without wiping the test site. After 15–20 minutes, the test sites were examined. The reaction was assessed by measuring the size of the wheal and the degree of erythema. A standard ruler was used to measure the wheal diameter. For concentric wheals, the diameter was recorded directly, while for non-concentric wheals, the mean of the horizontal and vertical diameters was calculated. The site was cleansed with alcohol after the test. A wheal measuring ≥3 mm more than the negative control was considered a positive test (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Table 1: Reading of skin prick test.

|

Wheal Diameter (mm)

|

Degree

|

|

< 3

|

0

|

|

3–3.99

|

1

|

|

4–5.99

|

2

|

|

6–8.99

|

3

|

|

≥ 9 or pseudopodium

|

4

|

Figure 1: Skin prick test positivity for MSG.

The data were coded and entered into a Microsoft Excel sheet and then analysed using the statistical software SPSS. Appropriate statistical tests, such as the chi-square test, were applied. Numerical variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. To study the correlation between urticaria and monosodium glutamate with study variables, the chi-square test was applied.

Results

Out of 120 adult patients with urticaria, 37 (30.8%) demonstrated a positive skin prick test (SPT) response to monosodium glutamate (Ajinomoto), indicating potential hypersensitivity. The remaining 83 patients (69.2%) tested negative, suggesting no allergic response to the substance (Figure 2). This finding highlight that nearly one-third of patients may experience exacerbation of symptoms with MSG exposure, pointing to its role as a potential dietary trigger.

Figure 2: Ajinomoto positivity.

Demographics and clinical correlates

The majority of participants were young adults aged 18–35 years (53.3%), followed by middle-aged adults aged 36–55 years (43.3%), and elderly individuals over 56 years (3.4%). The mean age was 37.1 ± 10.06 years. No significant association was found between age group and test response (p = 0.187). The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 48.3% males and 51.7% females. However, SPT positivity was significantly higher in males (39.7%) compared to females (22.6%), indicating a statistically significant association (Chi-square p = 0.043) (Table 2).

Table 2: Gender versus Ajinomoto SPT positivity.

|

Gender

|

Ajinomoto

|

|

Total

|

|

Positive

|

Negative

|

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

%

|

|

Male (n=58)

|

23

|

39.7

|

35

|

60.3

|

4.097

|

0.043

|

|

Female (n=62)

|

14

|

22.6

|

48

|

77.4

|

Of the total participants, 64.2% had acute urticaria (≤6 weeks), and 35.8% had chronic urticaria (>6 weeks). The average duration of illness was 10.09 ± 16.90 weeks. No significant correlation was observed between duration of illness and SPT response (p > 0.05). About 60% of participants reported symptom variation based on the time of day, but this did not significantly influence test outcomes (p = 0.628). A history of atopy was present in 20.8% of participants; however, this factor showed no significant association with MSG sensitivity (p = 0.187) (Table 3).

Table 3: Atopy versus Ajinomoto.

|

Atopy

|

Ajinomoto

|

|

Total

|

|

Positive

|

Negative

|

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

%

|

|

Yes (n=25)

|

5

|

20.0

|

20

|

80.0

|

1.738

|

0.187

|

|

No (n=95)

|

32

|

33.7

|

63

|

66.3

|

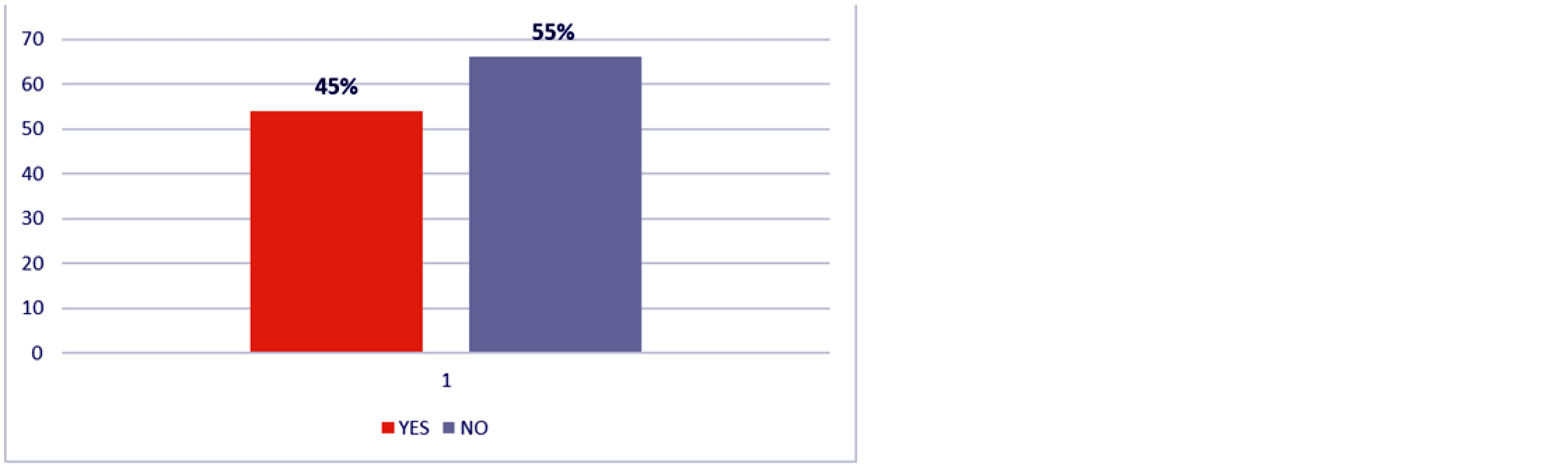

Regarding dietary history, 45% of participants reported recent intake of food from external sources. While this was not statistically analyzed, it suggests a possible link between food consumption patterns and urticaria flare-ups (Figure 3). More than half of the patients (56.7%) had no comorbidities. Among those with comorbid conditions, hypothyroidism (17.5%) was the most common, followed by diabetes mellitus (7.5%) and hypertension (6.7%). No significant association was found between hypothyroidism and test results (p = 0.584). Most patients (79.2%) were treated with antihistamines alone, 15.8% required both antihistamines and corticosteroids, and 5.0% needed a combination of antihistamines and cyclosporine.

Figure 3: History of food intake from outside.

Other clinical findings

A history of angioedema was reported in 17% of patients, but it was not significantly associated with the skin prick test response (p = 0.805). Dental caries was present in 59% of patients, indicating a high prevalence in this population. Anaemia was diagnosed in 21.7% of patients, but there was no significant correlation with SPT positivity (p = 0.626).

Discussion

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has long been associated with "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome" (CRS), characterized by symptoms such as headaches, flushing, and urticaria. However, scientific studies have not consistently supported a direct causal relationship between MSG and these symptoms. Most evidence indicates that fewer than 1% of the general population report sensitivity to MSG, particularly when consumed in large amounts or on an empty stomach.

Studies found no significant association between MSG ingestion and chronic urticaria [6-10]. Similarly, Subramaniam and Warner [2] observed urticaria symptoms in some patients following MSG intake, but methodological limitations in their study prevented definitive conclusions. In our study, 30.8% of urticaria patients tested positive for MSG in the skin prick test. However, no statistically significant correlation was found between SPT positivity and age, duration of illness, history of atopy, comorbidities, or diurnal variation.

Recent studies have provided valuable insights into the treatment and pathophysiology of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). In a 2021 real-world study, omalizumab monotherapy achieved a complete response in 66.9% of patients with antihistamine-refractory CSU, although those with lower baseline IgE and longer disease duration had a higher risk of early recurrence [11]. A 2023 review emphasized the growing role of biological therapies, particularly omalizumab and ligelizumab, which have demonstrated favorable efficacy and safety profiles in patients unresponsive to conventional antihistamines [12]. Furthermore, a 2024 study identified a rare subset of Lin⁻CD34⁺CD117⁺ progenitor immune cells in CSU patients, with higher levels of these cells correlating with improved responses to omalizumab, suggesting a potential predictive biomarker for therapeutic success [13].

These findings suggest that while a subset of patients may exhibit sensitivity to MSG, it is unlikely to be a major causative factor in chronic urticaria. The widespread belief in a direct link between MSG and urticaria may be attributed to recall bias, media influence, co-consumption of other allergenic substances, or cultural perceptions. Thus, urticaria exacerbations attributed to MSG are likely incidental rather than causal in most cases.

The study also reinforces that food allergens are rarely the primary trigger in chronic urticaria. Patients frequently attribute flare-ups to specific foods, including MSG, without clear objective evidence. Misattribution can lead to unnecessary dietary restrictions, anxiety, and impaired quality of life.

Key clinical recommendations

(1) Avoid blanket dietary restrictions involving MSG unless objective sensitivity is confirmed through validated diagnostic tools. (2) Educate patients about the low likelihood of food as a primary trigger in chronic urticaria and the difference between intolerance and true IgE-mediated allergy. (3) Utilize diagnostic methods such as skin prick testing, elimination diets, and oral food challenges to guide clinical decision-making. (4) Where feasible, perform double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges to distinguish genuine allergic reactions from perceived sensitivities.

Limitations: This study has a few notable limitations. First, the sample size of 120 patients may not adequately represent the broader urticaria population, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, as a single-centre study conducted in a specific geographical location, regional dietary habits and environmental factors may have influenced the results. Lastly, the absence of long-term follow-up and a double-blind placebo-controlled oral challenge limits our ability to definitively establish causality or sustained clinical outcomes related to MSG exposure.

Conclusion

Monosodium glutamate (MSG), commonly known as Ajinomoto is not a common or universal trigger for urticaria. In this study, only 30.8% of patients showed skin prick test positivity, while the majority exhibited no sensitivity. Therefore, blanket avoidance of MSG in urticaria patients is not justified unless sensitivity is objectively confirmed. Clinicians should focus on individualized assessment and patient education, emphasizing the difference between perceived and confirmed food allergies. Further large-scale, placebo-controlled studies are needed to better understand the clinical relevance of MSG in urticaria pathogenesis and to inform evidence-based dietary recommendations.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Latiff AHA, Baker D, et al. The EAACI/GA²LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2014; 69:868–887.

[2] Subramaniam S, Warner JO. Food additives and urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 1986.

[3] Genton C, Frei PC, Steiner P, Gfeller E. MSG-induced urticaria. Clin Allergy. 1985.

[4] Heinzerling L, Mari A, Bergmann KC, Bresciani M, Burbach GJ, et al. The skin prick test – European standards. Allergy. 2013; 68:702–712.

[5] Zuberbier T, Chantraine-Hess S, Hartmann K, Czarnetzki BM. Role of pseudoallergens in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 111:1016–1022.

[6] Simon RA. Additive-induced urticaria: MSG. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987; 80:530–534.

[7] Wilkin JK, Fortner G, Harris R. MSG flushing reactions. JAMA. 1980; 244:261–263. [8] Squire RA, Taylor RJ, Young EA. Angioedema following MSG challenge. Allergy. 1992; 47:313–316.

[9] Zuberbier T, Krause K, Maurer M, Church MK. Double-blind placebo-controlled food additive challenge in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000; 105:462–467.

[10] Itty AC, Rao PK, Sharma S, Thomas M. Skin prick test positivity for food allergens in patients with chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2022.

[11] Arnau AG, Pujol RM, Arnó AG. Efficacy of omalizumab monotherapy in chronic spontaneous urticaria: A real world, multicenter retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021; 35:245–247.

[12] Parveen R, Sharma S, Dogra S. Biologicals in treatment of chronic urticaria: A narrative review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023; 14:780–788.

[13] Teufelberger AR, Zink A, Hoetzenecker W. Extremely rare immune progenitor cells predict omalizumab response in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024; 153:1123–1131.